How do I write a morally gray serial killer?

I’m writing a character who is a serial killer but not willingly if that makes sense. Like, she kills once she finds herself in a murder or be murdered type of situation.. just wondering if you have any tips for writing such a complex character who kills but feels bad about it before, during and after the fact.

She doesn’t enjoy the act of murder. She doesn’t get off on it. She simply kills so she can survive.

This is a topic very close to my heart! I have a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice and a master’s degree in forensic psychology, both from accredited U.S. institutions. No fictional murder best-sellers under my belt, but it’s a topic I know a lot about.

Sometimes, people kill for reasons that aren’t nefarious. There’s the cut-and-dry self defense (“it’s me or them”), the culmination of years of abuse, or sometimes it’s completely an accident (which is called “involuntary manslaughter”).

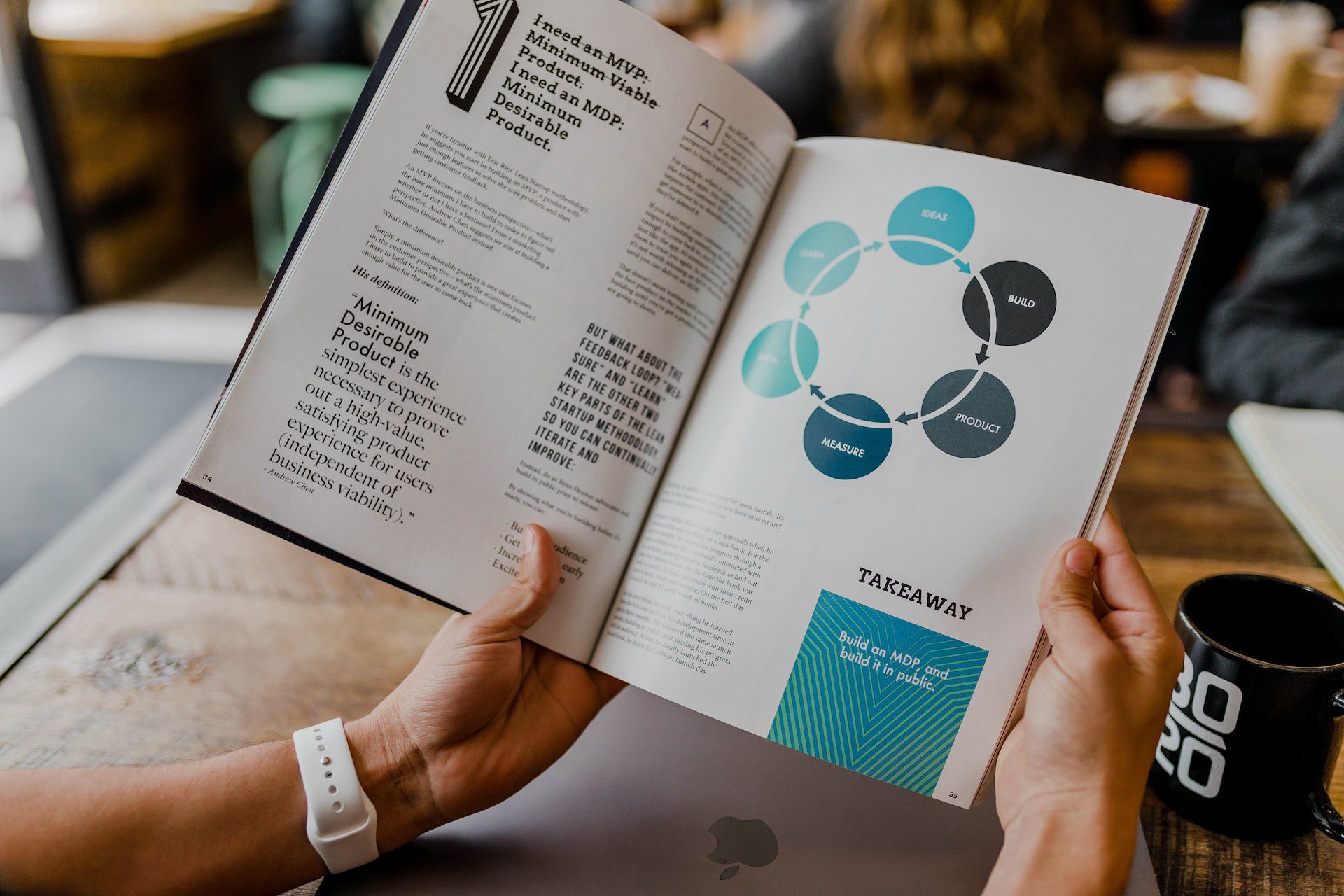

Murder mysteries and thrillers are top-notch reads and go hand-in-hand with pop culture’s fascination with true crime. But what goes into writing an accidental serial killer, or one that’s more upstanding than you’d think?

Define your morals

In order to establish morally gray, you’ve got to set the good and evil boundaries within the world you’re writing. Is it a modern-day story, where a cold-blooded killer is the evil one and a person defending themselves against an attacker is the good one? Or is it a more intricate fantasy or science fiction setting, where the laws and morals aren’t quite the same?

The important part of writing a morally gray character, in general, is establishing the normal bounds of morality in your story world and then placing the character’s values somewhere in the middle. They’re not looking to hunt other people for fun, but the act also wasn’t a noble defense or socially acceptable resolution to the problem. I think that’s the hardest part, building enough plausibility and setting up empathy for the character’s actions while still writing them as a ‘villain’.

The vigilante

The easiest example of a morally gray killer is the vigilante. Typically, their motive comes from a righteous or judicial point of view, and they’re killing the “evil” ones. These types are taking out drug dealers, abusers, or anyone committing what they consider to be egregious or immoral acts. They perform bad actions to do good.

Doing bad things for good reasons is often considered “lawful evil”, wherein a character is still following rules but they’re doing so in a ‘bad’ way. That circles us back to the beginning; there should still be a compelling reason for their actions. That’s what pushes their assigned morality back from ‘black’ into the ‘gray zone’.

Crossing the lines

Consider what factors or events would persuade a character to act in a worse or better way as a one-off circumstance, or a trigger that sways their actions. Perhaps they won’t kill parents, no matter what brought them into that position; maybe violence against women will often trigger a violent episode.

Gray, on the moral scale, has the obligation to be interesting — so don’t think too hard about staying within neutral territory. Swing one way or the other occasionally with good narrative build-up and support to really bring out the character’s individuality.

What if it’s always an accident?

Maybe your character is frequently caught in the wrong place at the wrong time, but they always manage to come out on top. What do you do then?

It’s first necessary to define a serial killer. Definitionally, a serial killer is a person that commits multiple murders. Murder being the key word — it must be on purpose for the act to fall on that definition. Otherwise it’s manslaughter (which is an incidental death where even if harm was meant, death was not). I can’t stress this enough: by definition, you can’t have a serial killer whose only kills were in self-defense or accidental. Your character must progress to proactive murder on more than one occasion for them to be considered a serial killer.

Of course, that’s not to say you can’t have other characters (or even their inner monologue) refer to them as a serial killer. Social knowledge rarely sees eye-to-eye with legal or academic terms and definitions. I just caution you against using ‘serial killer’ in marketing material or descriptive collateral, if this is the case. It is a technically inaccurate descriptor, and someone waiting for that switch from accidental to purposeful is going to be sorely disappointed when it never happens.

It could, however, be a great plot device to start there and explore the character’s evolution from unfortunate events to intentional murder. Maybe they were targeted for multiple violent crimes, and one day decided to be proactive and preemptively solve their problem (via murder, of course).

Avoid the Angel of Death

While a vigilante may be a good character type for the morally gray serial killer, the Angel of Death is not. This type of killer is looking for personal gratification by taking someone’s life into their own hands. More often than not, the Angel of Death is looking to make themselves a hero by saving the day, and the deaths are secondary (and a sign of their failure). I’ll admit that the line between “personal gratification” and “justice” can be a thin one.

The important distinction to keep in mind here are the moral definitions you’ve created: I can’t argue that an Angel of Death is serving any higher purpose than their own desire to cause situations where they might be a hero. It’s like hiring a hitman to take out a target, but intercepting the hitman just in time to save the target. The entire situation is at the mercy of the character; there’s no justice in the actions, no redeeming qualities. They don’t feel bad for sending the hitman — the outcome was planned from the start. And if they can’t beat the hitman? Oh well, better luck next time.

Convincing the reader that the protagonist has a good (“enough”) reason for their actions is key to achieving the moral middle ground. A reasonable, morally upstanding person probably won’t resort to the character’s actions, but they understand how the thought process could bring them where they are. The Angel of Death is fabricating the entire situation; a morally gray killer should be working towards a goal, or acting on a strong reason.

The morally gray serial killer isn’t looking to win anyone over, or get a standing ovation for their good deeds. They’re killing for a reason — a reason that wouldn’t normally drive someone to kill, but the reader can see how they got from point A to point B in the thought process.